Library Days 004: Ghost in the Shell (2017)

A Flawed But Visually Beautiful Place to Enter a Vibrant Intellectual World

I’m taking a break from writing about games this week to, instead write about a storied franchise with a lot of great content you can almost certainly find at a library, Ghost in the Shell. Right now’s also a good time to buy Ghost in the Shell media, with most of it being re-released (minus a few lesser titles) due to the big screen release of this week’s subject, Rupert Sanders new film adaptation staring Scarlet Johansson, Ghost in the Shell (2017). Spoilers follow.

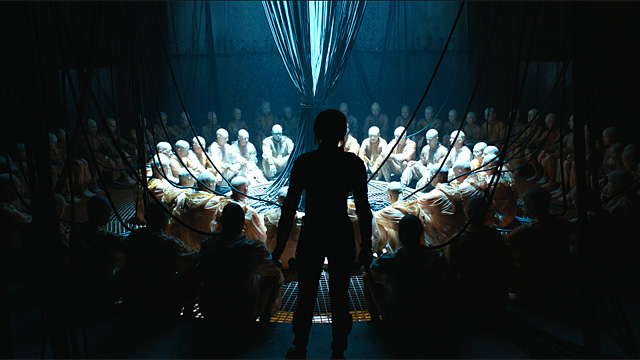

Ghost in the Shell follows Major Mira Killian, a woman rebuilt from the ground up as a cybernetic soldier, whose only original physical material is her brain. Repurposed by a corrupt corporation, Hanka, to fight domestic terrorists for the Department of Defense’ Section 9 in an unnamed future Asian city, the movie unfolds as a mystery where she must unravel the secrets of her missing past. When an enigmatic hacker named Kuze (Michael Pitt) begins killing Hanka officials, Section 9 is sent in, but Kuze is more than he seems, with connections to the Major’s past; helping reveal Hanka CEO Cutter’s corruption and connection to her missing memories. Along the way, she pals around with her partner, Batou (Pilou Asbæk), and the film beautifully re-enacts a lot of scenes from previous versions of the title.

And by re-enacts, I mean literal, shot-for-shot remakes of some of Japanese auteur Mamoru Oshii’s 1995 film’s gorgeously iconic action segments. Other elements are drawn from other adaptations, Hideo Kuze is the name of the antihero at the heart of the second season of the Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex animated TV show, 2nd Gig. 2nd Gig, it’s notable, was itself a thinly veiled remake of Mamoru Oshii’s 1993 animated political thriller, Patlabor 2. The depictions of Section 9’s staff are straight out of the original comics (if they are a bit more brusque, and less character driven). The opening action sequence of the movie directly references both the first episode of the animated TV show, and Mamoru Oshii’s second Ghost in the Shell Film, 2004’s Innocence (retitled Ghost in the Shell 2 in the English speaking world).

A lot of rancor has been had at the film’s superficial adaptation, and it’s massive whitewashing of cultural roles. In fact, it’s so blatantly a problem that it’s built into the plot. The Major and Kuze, it’s revealed in the film’s third act, were part of an anti-technology group of homeless Japanese youth—whose faces are never seen—kidnapped and experimented on by Hanka to create the perfect (and very much white) robotic soldiers. It’s a movie where the plot is literally the definition of cultural appropriation/whitewashing: an older white male businessman steals the identities of Japanese youths and remakes them as white people while erasing their ethnicity and stealing their mental labor. This is especially true of sections after The Major wakes up, where eye-liner has been clearly used to make the silhouette of Scarlet Johannson’s eyes more stereotypically Asian.

That’s pretty fucked up.

I can’t exactly say I’m surprised by the botched, tone-deaf adaptation; as it’s an Arad production. Producer Avi Arad’s background as a former head of Marvel Comics in control of its media properties, and producer of Marvel adaptations for 20th Century Fox, is responsible perhaps the spottiest and least defensible of any run of comic adaptation history, with highlights like the Singer X-Men films and Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man films; but for every one of those there were two Fantastic Fours, Ghost Riders, or the Affleck Daredevil and its Elektra spin-off, to completely bewilder filmgoers with their terrible decisions. Arad has recently turned his attention to the booming games industry, and has the film options for both Metal Gear Solid and Uncharted franchises to frighten fans with a general misunderstanding of the interesting parts of those properties.

It’s hard to ignore the blatant problems of cultural appropriation/whitewashing in the 2017 film. Outside of those, it’s fascinating as a loving pastiche of prior animated films and comic adaptations; and it’s clear some work has been done to maintain a sense of character and style relating to the source material. The American film muddles certain ideas, and seems desperate to create a too clean version of the Blade Runner inspired Newport City/un-named city in the film. One thing about Ghost in the original comic and films is that it was a dirty, teaming city, full of cultural disparity; it’s outright filthy and there’s constant detail of people trying to get along with their workaday, personal lives.

It’s worth noting that Motoko Kusanagi, in just about all configurations, is a queer character. In the new film, this relates to a scene as Motoko picks up a woman on the street, loosely implied to be a sex worker, and explores her body in a sensual way (this scene included a kiss that was shown in trailers, but was cut from the final film) that is the film’s lone exploration of The Major’s sensuality. This is a nod to the series—if it can be seen as queer-baiting—going all the way back to the original work’s prurient sex scene that’s handled as a bit of a joke, as Batou discovers her in virtual flagrante dilecto with a pair of women, when he spies on her inadvertently while she’s on vacation when he has to get her go ahead for a Section 9 operation.

In his notes for the art book Intron Depot, which includes this sex-scene that’s excluded from English language releases of the comic, original author Shirow notes in an expression of backhanded homophobia that he made it an all-woman sex scene because he didn’t want to draw some guy’s butt, and didn’t want to draw tentacle sex porn. It’s been more than a little bit of a gift to queer representation in Japanese media (and her relationships with other women are further explored in the televisions show) as The Major’s sexual identity has become more complex for a one-off joke. It’s not the first time Japanese pop media has created fascinating queer women through latent male homophobia; the great queer anime, Revolutionary Girl Utena, has a lesbian relationship at the center of it because co-creator and director Kunihiku Ikuhara thought fans would prefer watching two teen girls get together romantically than a girl and a guy.

Motoko Kusanagi’s presentation and identity in Oshii’s original films has an asexual or agender quality that matches the concept throughout the films, identifying her as a doll brought to life by the errant “Ghost”—her brain having been placed into a synthetic body with superficial secondary sex characteristics (a shot of her body floating in the intro lacks genitals or nipples; and in one of the film’s most iconic montages, Motoko travels through the city and sees herself reflected in the bodies of fashion store mannequins that are increasingly featureless)—and she ascends beyond gender when melding with the masculine Puppeteer AI (Puppetmaster in the 1995 film) at the end of the film and book; which Oshii contrasts by placing her in a designated-female body and Victorian dress after her revival. The original comic does much the same, but in reverse, when Motoko informs Batou that the black market cyborg body he supplied as a replacement for her destroyed body, is male designated. In the first season of the television show, there are inferences that Motoko is a transgender woman, who was designated male at birth, before requiring a replacement cyborg body. In any case, Motoko Kusanagi’s gender, in addition to the general transhumanist narrative elements, has transgender elements of crossing or absorbing multiple genders through the unification of multiple intellectual, emotional, sexual, cognitive identities. Even the new film implies that she links at least partially to Kuze’s network of living human brains at the end of the film, when he uploads his consciousness to the network while staring into her eyes.

If there’s one confusing thing about Ghost in the Shell in any iteration, it’s just what exactly a “Ghost” is supposed to be. In the new movie it’s described as a soul, but even that is pretty nebulous, and the villain at one point decries the frailties of the “human heart” before shooting someone in theirs. In a sense, this would align the “Ghost” more with the Japanese concept of the heart, “kokoro”, and the Mexican similitude of “coraźon” , in the pop media of both cultures, where “heart” is a stand-in for emotional intelligence and depth of feeling. The 2017 movie is clearly conflating this concept with the concept of true memories and core subconscious truths—the film shows Motoko’s brain, and suggests that it’s consciousness can be digitally overwritten, even though the brain itself is intact and hasn’t been replaced by what Shirow and Oshii eventually referred to as “an e-brain” or replacement of the conscious and memory centers of the brain with synthetic, digital material.

In the original Japanese works, “Ghost” is a bit less of a nebulous conscept, but more infuriatingly abstract; in Shirow’s end-notes for the original comic, he writes that the ghost is a combination of the body and mind to create the present state of being, so the “ghost” wouldn’t be just our pure consciousness, but also the sensations and feelings of the body itself combining to create the whole mental state. The greater implication is this includes the intuitive “gut” parasympathetic nervous tissue that acts as our “second brain”, and subconscious brain activity, rather than pure consciousness and retrievable memory. When Section 9 discovers that the artificial intelligence known as The Puppeteer has a ghost after transferring itself into a cybernetic shell with no brain, this definition implies that the Puppeteer had no ghost until it downloaded itself into a body; because it lacked the connections to a concrete physical state, and a sense of mortality. That the Puppeteer could download itself into a body implies it could potentially replicate, online, the presence of a Ghost without the necessity of a body. So when it offers to merge with Motoko Kusanagi, what it’s offering is a means of creating digital progeny through cloning herself, and proliferation through the incremental replacement of physical brain material with cyberized parts. Side note: this would give transhumanists and singularity enthusiasts raging mental boners if any of them clearly understood it (yes, I am throwing major shade on the bulk of the transhumanist community that believes that they wouldn’t die by creating a digitial copy of their consciousnesses; the individual meat-you would not magically transfer its consciousness just by creating a copy, and you still will die when your body dies, meatbag). Oshii presents a similar idea of “Ghost” to Shirow’s where it’s most often used to reference the subconscious; when acting on a hunch Kusanagi quips, “I can feel it in my Ghost.” as if her Ghost is a separate, deeper intuitive or holistic identity to which she has a connection, but not complete access.

That depth, in spite of superficial recreations of interesting scenes in the Japanese works, never quite materializes in the American adaptation. It trades in deeper questions about identity for the assurances that finding your point of origin is enough to find emotional solace; i.e., Major finds her mother, and revealing her identity allows her to continue forward in her life with confidence. It’s fine, I guess, but it misses the majority of what made the series fascinating and interesting to others. Luckily, you can absolutely read/watch most of it, since it’s been translated into English. Here’s a list of stuff to look for at your library!

The Original Comics:

Ghost in the Shell (1989-1990) by Masamune Shirow

Amazon Link: http://a.co/49AY42n

Ghost in the Shell is a series of interconnected comic short stories about a group of police officers/investigators Public Security Section 9 (think a cyber-division of the FBI, with implants that allow them to connect their brains to the internet) set in the year 2029. Most of the stories focus is on Major Motoko Kusanagi, the ranking member of the team, and Division 9’s investigation of a mysterious hacker known as The Puppeteer. The story spans questions of personal identity and the future of international politics in a more connected, digital world.

Other elements include the advancement of thinking and feeling subservient artificial intelligences (Section 9 uses AI’s mini-tank robots known as Fuchikomas) and autonomously developing intellectual beings (the Puppeteer, project 2501) and questions of the nature of consciousness.

Ghost in the Shell 1.5: Human Processor Error (1991-1996) by Masamune Shirow

Amazon Link: http://a.co/h5Lt8fc

Between the release of Ghost in the Shell, and Ghost in the Shell 2, Masamune Shirow released a series of short stories following the departure of Major Kusanagi from Section 9 at the conclusion of the original comic. These stories, set a few years after the original, are fairly self contained, but form the backbone for the feel of later Ghost in the Shell media, especially the animated television show.

The stories mostly focus on The Major’s goofy former partner, Batou, his new partner Azuma, and now seasoned investigator Togusa. Motoko Kusanagi (or a copy) appears briefly in one segment as a mercenary using the alias Chroma Aramaki, and her appearance bridges the gap between the events and characters of Ghost in the Shell 1 and 2.

Ghost in the Shell 2: Man Machine Interface (2001-2005) by Masamune Shirow

Amazon Link: http://a.co/hcQuF0j

Shirow baffled fans of the original comic by releasing a story that seems mostly disconnected from the original series, set in 2035, about a mercenary and information broker named Motoko Aramaki. More spiritual and esoteric than it’s predecessors, it shares more in common with his over-the-top fantasy comic, Orion, than it does with prior Ghost in the Shell comics.

This is pretty heady transhumanist stuff, that’s built on the assumption that the reader understands the implications of The Major merging with the puppeteer at the end of the first comic, and the bulk of the dialogue can sound like technocratic word salad if you can’t keep it straight in your head, or alternatively don’t have access to a glossary of terms Shirow has used in the past. This is especially true of the end, where Shirow makes the attempt to synthesize principles of Shinto spiritualism with the idea of an emergent silicone lifeform born out of digitization—this is where it dovetails with Orion most heavily in terms of cultural translation problems (in Orion Shirow combined kanji (Chinese characters) in ways to create double or tripple-meaning puns that don’t translate into English particularly well, while referencing Japanese myth).

A note on this title: This is a seinen title (or Japanese men’s comic). It is definitely for adults, and is geared towards an adult Japanese male audience, with the images clearly designed to be sexually titillating (in the late 90’s Shirow went from being a comic artist to mostly a narrative designer/art director for games/animation, and pin-up artist, so his later work is much more sexualized; including outright pornography; much to the chagrin of some former fans). Again: definitely not for kids.

Original Anime Movies/Novelizations

Ghost in the Shell (film, 1995) dir. Mamoru Oshii.

Amazon Link: http://a.co/alQASOS

One of the first US/Japan anime coproductions, this 82 minute anime adaptation is a contemplative vision from Japanese auteur Mamoru Oshii, that focusses on the more introspective aspects of the comic with a series of action vignettes broken up by introspective montages.

This is what most people think of when they think of Ghost in the Shell.

Innocence (AKA Ghost in the Shell 2, film, 2004) dir. Mamoru Oshii.

Amazon Link: http://a.co/7n4VHHh

Oshii’s longer, philosophical, most indulgent anime film is a loose adaptation of one of the other original stories in the first Ghost in the Shell comic. It’s set three years after the original film, and follows an emotionally bereft Batou trying to make sense of the world (and his own sense of grief and disaffection) following the Major’s disappearance at the end of the first film. He and partner Togusa investigate crimes by robotic geisha, that before being destroyed beg the team members to “save them.”

Much of the design of the new live action movie is adapted from this movie.

Innocence: After the Long Goodbye (novel, 2004) by Masaki Yamada.

Amazon Link: http://a.co/4ngtgR5

Rather than write his own novelization, Oshii asked Japanese sci-fi novelist Masaki Yamada to write supplemental book to his film Innocence. After the Long Goodbye is a prequel that happens directly before Innocence, in which Batou’s prized basset hound, Gabriel, goes missing, not recognizing him after he forcibly reboots his hardware and his “soul” goes missing for a short time after the reboot. Batou’s search for his missing dog draws him into a terrorist plot involving a local crime lord and a master terrorist manipulator.

Stand Alone Complex: TV Series/Movie

Ghost in the Shell: Stand-Alone Complex (TV series, 2002-2003, 26 Episodes) dir. Kenji Kamiyama

Amazon Link: http://a.co/5AKc9di

Set in an alternative reality than the films: The first season of Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex is a mix of stand alone episodes and an overarching story about The Laughing Man, a hacker who covers his identity with a smiling face and a scrolling quote from J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. When the Laughing Man reappears following an absence of years, Public Security Section 9 investigates. As a TV show, GITS:SAC has more time to explore the characters and concepts of the comics and films in more depth.

Stand Alone Complex was created by Team Oshii under the advisement of Mamoru Oshii, with the cooperation and input of original creator Masamune Shirow, prompting some to consider it the most “official” adaptation of the material. It introduces robots similar to the Fuchikomas, called Tachikomas, and lifts one story arc about them, and its dialogue, directly from the original comic. Director of the TV series, Kenji Kamiyama (Eden of the East) said that he copied Oshii’s directing style when making the series.

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex: 2nd Gig (TV series, 2004-2005, 26 Episodes) dir. Kenji Kamiyama

Amazon Link: http://a.co/7Jov5Fs

Again a mix of stand alone and story episodes, the main arc, Individual Eleven, focusses on a refugee crisis after the economy recovers following World Wars III and IV. Much of this arc focusses on Major Kusanagi’s relationship to Hideo Kuze, a full body prosthetic soldier abandoned after the war with whom she shares a particular emotional bond. The plot of this arc is a loose remake (right down to character relationships) of Mamoru Oshii’s early 90’s film, Patlabor 2.

This season’s ending, with the Tachikomas reborn as Fuchikomas, and the characters wearing the comic’s iconic body armor, establishes the series as a prequel to the original comic.

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex: Solid State Society (film, 2006, 3D conversion 2010) dir. Kenji Kamiyama

Amazon Link: http://a.co/5kRIQtK

Set 2 years after the events of 2nd Gig, and the events of the original comic, Solid State Society involves an investigation into a copy-cat Puppeteer by Section 9 and an independent Motoko Kusanagi who has merged with the original Puppeteer.

Ghost in the Shell Stand Alone Complex (comic, 2009-2012) by Yu Kinutani

Amazon Link: http://a.co/5Aejwxe

A straight adaptation of episodes of the first series of Stand Alone Complex into comic form.

Ghost in the Shell: S.A.C. – Tachikomatic Days (comic, 2010) by Mayasuki Yamamoto

This manga series is a series of gag strips based on comic shorts featuring the Tachikomas that followed episodes of the TV show.

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex (novels, 2004-2005) by Junichi Fujisaku

Amazon Link: http://a.co/3khbOu7

Three Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex novels have been translated and released in English: Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex – The Lost Memory (2004), Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex – Revenge of the Cold Machines (2004), and Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex – White Maze (2005).

Arise Mini-series/2nd TV series/Movie

Ghost in the Shell: Arise (2013 – 2015, mini-series, 4 episodes) dir. Kazuchika Kize

Amazon Links: Episodes 1 & 2: http://a.co/j3wUIBj Episodes 3 & 4: http://a.co/dbmznlq

A prequel mini series made up of four, hour-long episodes that received a limited theatrical release. Arise establishes how Public Security Section 9 was created and its early cases.

Ghost in the Shell: Arise – Alternative Architecture (2015, TV show, 10 episodes) dir. Kazuchika Kize

Funimation Streaming Link (subscription necessary): https://www.funimation.com/shows/ghost-in-the-shell-arise/

Alternative Architecture edits the Arise miniseries into a short televisions series, cutting the four episodes into eight 22 minute episodes, and adding two new segments that form a fifth arc to the series, “Pyrophoric Cult.”

Reviews have not been kind for the adaptation. The episode order was changed, and since each episode was nearly an hour long, but had to be cut into two 22 minute episodes, a lot of material had to be cut out. However, there has been praise for the extra two final episodes, which add to the series’ lore and help set up the movie that ends the series.

Ghost in the Shell (AKA Ghost in the Shell: The New Movie, film, 2015) dir. Kazuchika Kize

Amazon Link: http://a.co/9rnKNML

This film wraps up the Arise arc, and leads directly into the 1995 Ghost in the Shell movie.

GAMES

Ghost in the Shell (3rd Person Shooter Game, PSX, 1997)

Designed by Masamune Shirow for the Playstation 1, this third person game puts you in control of a rookie character from Section 9, controlling a Fuchikoma mini-tank. It has a lot of references to Shirow’s 80’s and 90’s comics, and is broadly comical; worth playing for Shirow fans. May be hard to find in disc form, but surely exists as a ROM (a filetype that can be played on a console “emulator” on a computer).

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex (Third Person Action: PS2, 2004, First Person Shooter, PSP Sequel, 2005)

Set between the first and second seasons of Stand Alone Complex, these games feature original stories set in the same universe.

Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex: First Assault Online (Online Multiplayer First Person Shooter, PC, Free-to-Play, 2015 early access, 2017 full release)

A squad based online shooter based in the world of Stand-Alone Complex, set for full release later this year.

Parody Comics:

Pandora in the Crimson Shell: Ghost Urn, (manga, 2009-present. Original Animation, 2015, TV series 2016, 12 episodes) story by Masamune Shirow, art by Kōshi Rikudō.

Amazon Links: Manga: http://a.co/gpcH3aK Anime: http://a.co/7fRkmfm

Masamune Shirow was hired by an anime production company to write and design an anime/manga series about young girls with prosthetic bodies. During the process, he suggested that someone else draw the comic due to his style being unsuited for the concept of the material, and that it might be too similar to his prior Ghost in the Shell comics. Excel Saga creator Kōshi Rikudō was brought on to develop the material further and make it more accessible.

Pandora centers around first generation full body cyborgs Nene Nanakorobi and Clarion, and their relationship. Nene think Clarion is adorable, and emotionless Clarion can open up Nene’s natural “Adepter” abilities as a cyborg, by letting Nene draw combat information from her by touching the port on the end of her finger to an opening at Clarion’s crotch (Pandora, like the Ghost comics, is a “Seinen” or men’s comic, so beware that it has content purely for men’s titillation and is not intended for young audiences). Pandora has a more conventional manga/anime structure and pacing than other Shirow projects, with characters who are fit much more standard anime/manga tropes.

It has a number of jokes making fun of Ghost in the Shell. An early fight with a mech can only be ended by putting a pair of glasses onto its control interface, which looks like the cyborg body the Puppeteer downloaded itself into at the end of the original comic. Instead of Fuchikomas, it has spoof Gertse-Kommas, etc. Pandora has been criticized for being crass and tone-deaf, but does not seem to be that different in tone or style from other contemporary Seinen gag comics (i.e. either this is former fans targeting Shirow for switching his career to becoming a pornographer—he drew some explicit furry porn, who cares?—or they don’t know that the entire genre is tone deaf and crass, because Japanese society is decades behind the west on women and minority rights).

Upcoming Projects

New Ghost in the Shell Anime

It’s been announced that Stand Alone Complex director Kenji Kamiyama, and Shinji Aramaki will direct a new Ghost in the Shell anime project. Format and style are yet to be announced (Aramaki, who produced the original Oshii film, has adapted one of Shirow’s other mangas, Appleseed, as a CGI series of films, and Kamiyama directed CGI adaptations of classic manga Cyborg 009).

Honorable Mentions:

Avalon (2001) dir. Mamoru Oshii

Import Blu Ray Link: http://www.blu-ray.com/movies/Avalon-Blu-ray/14881/

Between his Ghost in the Shell films, Mamoru Oshii made Avalon, a live action film made in Poland (in Polish) for a Japanese audience. The movie is about Ash (Małgorzata Foremniak), a woman who makes her living fighting in a first-person shooter virtual reality game called Avalon, who discovers the game may be playing her, rather than the other way around. Ash is based loosely on Oshii’s version of Major Kusanagi, and faces similar issues of identity and questionable reality.

Doomsday (2008) dir. Neil Marshall

Amazon Link: http://a.co/5PqzE0G

Scottish film and television director Neil Marshall (known for horror films like The Descent, and TV episodes of Game of Thrones, Hannibal, Westworld, etc) made this post-apocalyptic film about an operative, Major Eden Sinclair (inspired by Major Kusanagi) who leaves the safety of a sealed city decades after a global pandemic, to find a rumored cure beyond the reach of barbarian hordes, after the virus resurges.